Hi friends, Better late than never: MERRY CHRISTMAS and a Happy New Year :). I am on my annual 7 week social-media fast…. but I always leave leeway for email updates during the break 😉. Here is what’s happening behind the scenes (with 2 books I am loving right now at 30% off).

This month I learned how to use my meat saw. This one is on sale for $80 off right now. (nope, I’m not earning commissions on that link, but if sharing about the discount helped you you can buy me a coffee with some of your savings.😉)

BUTCHERING (the lamb and goat version) has been my go-to as I slowly learn butchering side of shepherding. Buy the book for 30% off (and free shipping) HERE.

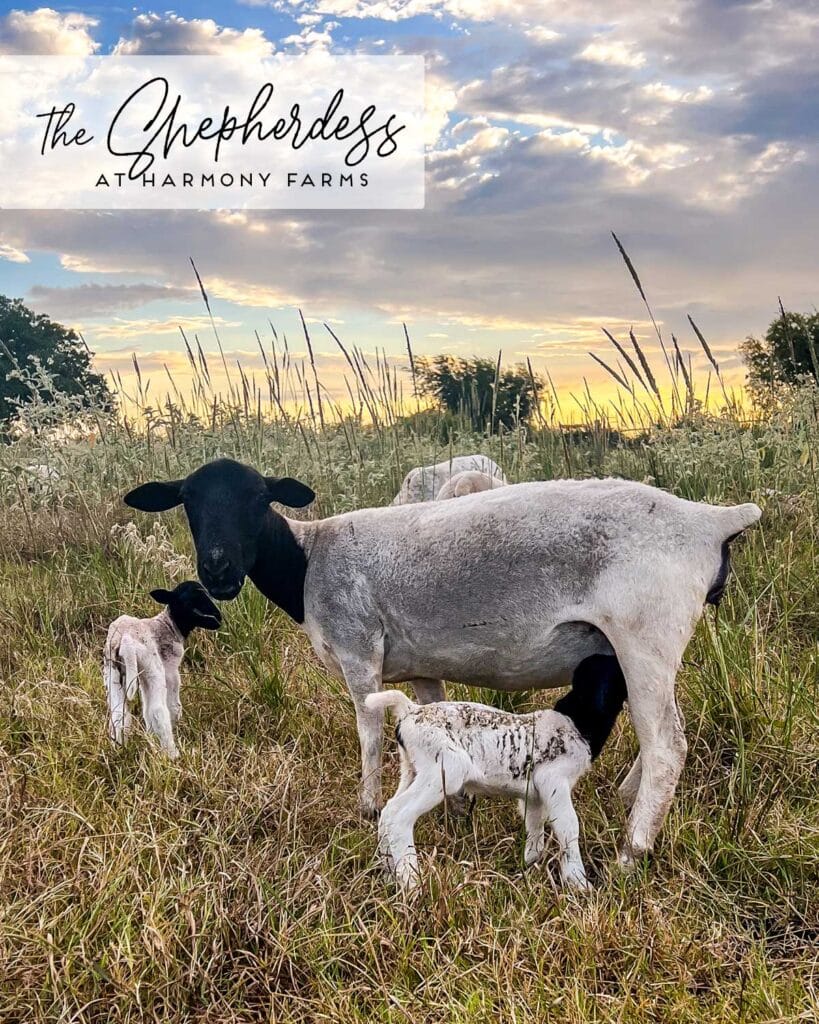

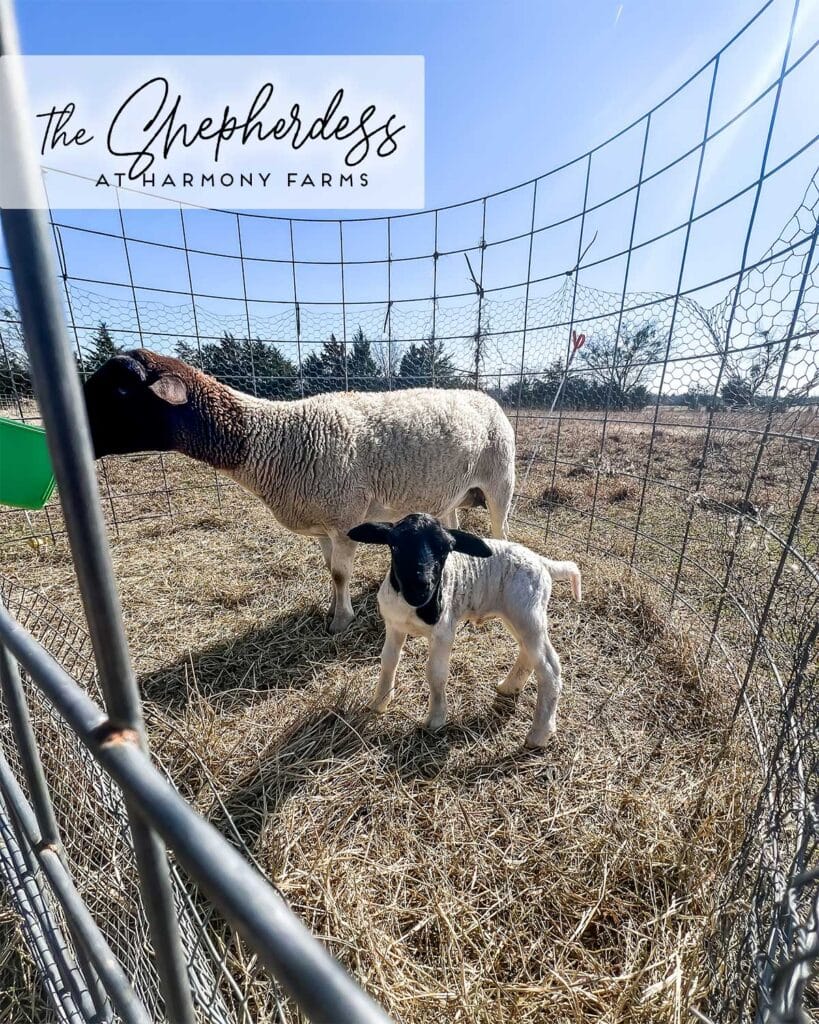

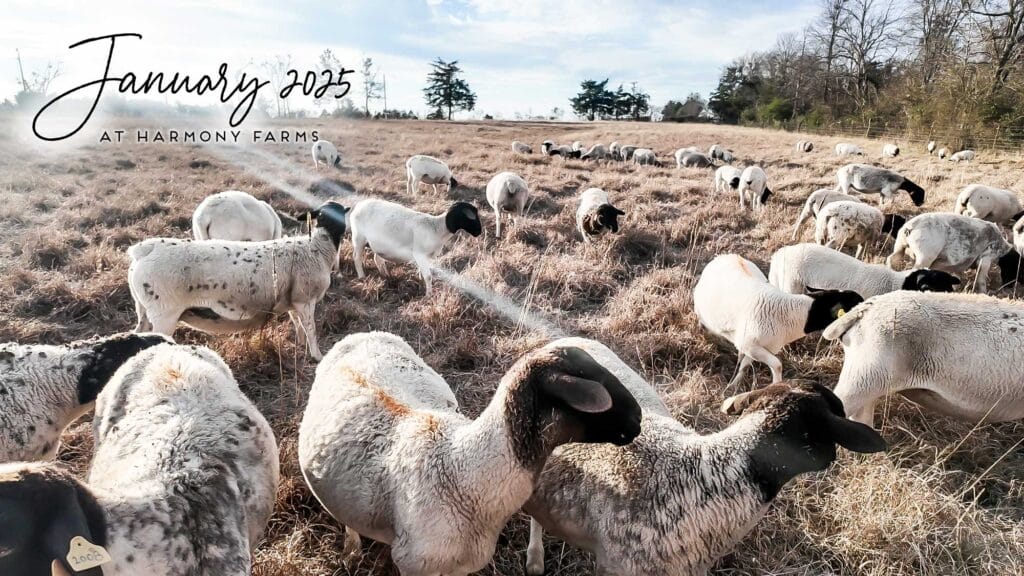

Lambing season kicked off (yep, winter lambing is a Texas advantage). Twinning rate is way up and ewe lambs are leading on a 9-1 ratio! This is good news for those on my waitlist for ewe lambs!I plan to open reservations for breeding stock in February. Prayers for Lazarus (the little guy not standing) would be appreciated. I found him 1/2 frozen and the verdict is still out as to whether or not he will “come forth”.

It takes 12-18 gallons of quality milk to raise one lamb. (which translates to about $250 per lamb when I buy goat milk at retail) Instead of buying milk, I use 2 dairy goats to build up a milk bank over summer. These girls definitely earn their keep!

Raising Goats Naturally has been my favorite book for Dairy Goats. Buy the book for 30% off (and free shipping) HERE.

Keep at it, everyone. ❤️ -the Shepherdess “But my God shall supply all your need according to his riches in glory by Christ Jesus.” Phil. 4:19 |

Surprise 😍

If you are like me, you are… ahem… a bit last minute. 🎁 So in honor of you (and me 😉) I am hosting a FLASH SALE on select homestead books, children’s books, and STOCKING STUFFERS: $2 and $7 with $10 FLAT RATE PRIORITY SHIPPING! HURRY, order deadline is THURSDAY at 12pm! I plan to ship everything on Thursday afternoon via PRIORITY MAIL. While I cannot guarantee USPS service standards, I will be packing and shipping for best chance for delivery by Christmas!!!

“Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, and cometh down from the Father of lights, with whom is no variableness, neither shadow of turning.” James 1:17 |

How I Keep Records on My Small Sheep Flock

How to Breed a Low-Maintenance Sheep Flock (My Simple Record-Keeping System)

In this post, I’m going to walk you through the simple record-keeping system I use to manage and improve my small flock of sheep. This system is designed for flock sizes anywhere between 6 and 100 — small by industry standards, but large enough that organization truly matters.

I’ll cover:

- My ear-tagging guidelines

- What information I track

- How I organize those records

- And how this system helps me breed a low-maintenance, resilient flock year after year

If you raise sheep or goats, I want to encourage you to download my FREE Beginner Shepherd Resource Bundle. It’s an ebook that covers the three pillars of success with small ruminants:

- Raising sheep

- Rotational grazing

- Marketing sheep for a profit

Click the first link in the video description, and I’ll email it to you for free.

A Quick Disclaimer

This is my system, and it works extremely well for my style of grazing and flock size. If you have variations, additions, or ways to improve upon it, share them in the comments — your insight might help someone else refine their own system.

Context: Why My Record Keeping Is Simple

My flock is still under 100 sheep, and after five years of culling hard for low-maintenance genetics, I simply don’t have many health issues to track anymore.

In the early days, I kept more detailed notes because… well, there were more problems.

But today, my sheep are extremely low-input, so my record keeping is:

- Simple

- Cheap

- Effective

All I use are three tools:

- Ear tags

- A daily planner

- Google Sheets

That’s it.

1. Ear Tags: The Foundation of My System

Everything starts with tagging lambs at weaning. I use simple Allflex ear tags (orange is my favorite color for visibility).

My numbering system always begins with:

- The year, followed by

- A sequential number starting with 01

Example:

If I have 70 lambs born in 2025, the tags will run from 2501 to 2570.

Tagging by year is incredibly helpful because I can look at any ewe and instantly know her age. That matters when evaluating health issues — an eight-year-old ewe with minor ailments is not the same concern as a two-year-old with recurring problems.

2. The Daily Planner: Where Raw Notes Live

My daily planner is where I jot down everything as it happens. The types of details I track include:

- Births

- Deaths

- Ailments (hooves, worms, limping, etc.)

- Treatments or supplements of any kind

- Breeding details:

- Ram joining dates

- Removal dates

- First lambing date

- Last lambing date

Whenever possible, I reference tag numbers. For example:

- 1909 had twins on the 5th

- 2304 was limping and needed Hoof & Heel

These quick daily notes become the raw material for my long-term tracking.

3. Google Sheets: The Master Record

Once per month (or sometimes once per quarter), I take all those daily planner notes and enter them into my Google Sheet.

My setup is simple:

- One tab per sheep

- Notes added line-by-line throughout the year

This sheet becomes my end-of-year evaluation tool. Each winter, I cull the bottom 10–20% of the flock based on the data in this spreadsheet. The “bottom” sheep are the ones who:

- Required the most deworming

- Needed frequent treatments

- Struggled with feet or condition

- Needed supplementation that others didn’t

By reviewing each sheep’s tab, the top performers rise to the front, and the bottom performers become obvious.

This is the backbone of how I improve my flock every single year.

Why This System Works

This method is:

- Low cost

- Beginner-friendly

- Highly effective

- Scalable up to around 100 ewes

Most importantly, it keeps me focused on breeding a flock of sheep that thrives with minimal intervention. My system doesn’t reward the sheep that need the most help — it highlights the ones that do well naturally.

That’s how you build a low-maintenance flock.

And if you’re curious about the real costs of raising sheep, be sure to watch the next video — The 15 Costs of Raising Sheep.

HOW TO MAKE A BUSINESS OUT OF FARMING (3 Tips)

This video shares 3 business tips for new farmers from Joel Salatin’s Polyface Farms model!

1 HOUR INTERVIEW WITH Joel Salatin: https://bit.ly/2022atPolyface

Finding Lease Land using onX: • HOW TO FIND LEASE LAND FOR FARMING & RANCH…

Join my Newsletter: http://bit.ly/ShepherdessNWSLTR

SALAD BAR BEEF BOOK: https://bit.ly/SBBeefBOOK

How to Go Full Time in Farming (from the Polyface Farm Business Model)

There are three primary challenges small farms face today if they want to be profitable — not just an expensive hobby:

- Access to land

- Human resources

- Cashflow

During my visit to Polyface Farm, I saw firsthand how Joel Salatin’s unique business model tackles all three of these obstacles. In this post, I’m going to show you how the Polyface example can help beginner farmers break through these same barriers.

How Polyface Inspired My Own Farm Journey

When I first jumped into agriculture, Joel Salatin’s book Salad Bar Beef gave me the confidence that I could raise livestock profitably on just 30 acres — even as a complete beginner.

I read that book nearly six years ago. Three years later, I went full-time in agriculture on my own 30-acre enterprise. I had zero prior experience, and while my journey took a turn away from beef and toward sheep (a better fit for small acreage), I scaled my revenue and built a full-time farm by mirroring key parts of the Polyface model — not just the meat production side, but also Salatin’s value-added enterprises.

For those unfamiliar, the Polyface business model is radically different from the conventional farm model. Joel routinely catches criticism from the “farm establishment,” largely because he refuses to leave money on the table. Polyface isn’t just a meat farm — it’s also an agritourism hub, an educational platform, and a mentorship ecosystem.

Small farmers willing to follow this example quickly discover something powerful:

Inviting people to interact with your farm not only widens margins — it fulfills a deep cultural hunger for connection to land.

As you read through these three challenges and three Polyface-inspired solutions, I encourage you to identify at least one unconventional idea you can apply to your own farm. Drop a comment telling me which one resonates most with you.

1. Land Access: Getting a Foot in the Door

The price of land today makes it nearly impossible for a beginner to purchase acreage outright — at least, not with farming income alone. Thankfully, Salatin highlights three practical pathways for securing land access without shelling out hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Option 1: Steward Family Land

Landowners are aging, and many end up selling only because no one is willing to carry their vision forward. This was my route.

I don’t own my farm. I lease 30 acres of family land for my sheep enterprise.

It has been a win-win: I have access to land I could never afford to purchase, and my family has someone maintaining the property.

Option 2: Lease Land from Strangers

This option is similar to the first — just without the family connection.

I’ve secured several short-term leases this way (I’ll link the full step-by-step video below). Yes, cold-calling landowners is uncomfortable… but you get over it.

My method:

- Use OnX Hunt to find the landowner’s name

- Track down a phone number through community connections or

- Send a letter requesting a lease

Option 3: Inheritance

This is the least common path — most of us aren’t inheriting hundreds of acres.

Joel himself took over Polyface from his father, who purchased it as a worn-out, degraded piece of land. Joel chose to carry forward his father’s vision and build upon it. That willingness to steward legacy is often lacking today, which is one reason many landowners choose to sell rather than leave property to their children.

2. Human Resources: Solving the Labor Crunch

New farmers often start with enthusiasm, juggle every role themselves, and burn out within a few years. The Polyface model solves this through a self-feeding labor pipeline built around two components:

- Seasonal mentorship programs (“Stewards”)

- A small core of year-round staff

The Steward program brings in young people to live and work on the farm during the busiest season: late spring through early fall. These individuals gain hands-on experience and contribute enormous labor value exactly when the farm needs it most.

Stewards work for room, board, food, and mentorship rather than cash — and the very best are sometimes invited to join the full-time paid staff.

This model is ingenious, sustainable, and absolutely repeatable — even for tiny farms.

3. Cashflow: The Polyface Superpower

Cashflow is my favorite topic — and the one I studied most closely while building my own enterprise.

Polyface is not a commodity farm. They don’t sell grain to elevators or livestock at auction. Instead, they operate a direct-to-consumer meat business, selling:

- Pork

- Chicken

- Eggs

- Lamb

- Turkeys

- Rabbits

These are sold through online ordering and local buying clubs, with scheduled delivery drops in affluent, health-conscious communities in Virginia.

But what really widens their margins is the value-added enterprise stack layered on top:

- A farm store with merch and local goods

- “Lunatic Tours” at $25 per person

- Multi-day on-farm seminars

- Self-published books (over 100k copies sold)

- Paid speaking engagements

Not all of us are Joel Salatin–level personalities, so some of these opportunities may not translate directly.

But after interviewing Joel in 2021, I challenged myself to see how many I could adapt as a complete nobody — a brand-new farmer with no credentials.

Here’s what that looked like for me:

- Instead of a physical farm store → I built an online store with handcrafted merch

- Instead of weekly on-farm tours → I publish weekly YouTube videos (digital agritourism)

- Instead of hosting on-farm seminars → I host live online workshops

- And I self-published a book on sheep farming

All of these became meaningful revenue streams that buffer my farm income through the ups and downs of startup life.

If you can find even one unique income stream outside raw food sales — a value-added product, an educational angle, or a digital version of agritourism — your farm’s cashflow becomes far more resilient.

Ready to Take the Next Step?

If you want to see exactly how I scaled from $0 to $100k on a 30-acre beginner farm, watch the next video where I break down the entire process step-by-step.

Meat (sheep) Stats 🐑🥩 | How Much Meat do Dorper Sheep Produce?

Hi Friends,

October was pretty low-key on pasture, but I sent a few lambs to processing. I will share meat stats and recipes below! 🐑🥩 Thank you to everyone who purchased during my Autumn livestock sale. Breeding stock is sold out for 2025. Next availability is looking like February 2026!

| Grass fed lamb: 110lb at roughly 10 months old. |

I sent a group of meat wethers off to processing in October. I aim for 100lb live weight before sending to the butcher, but 90 lb is also a good average.

My best bloodlines will hit this weight on mom’s milk and forage only by about 9-10 months.

A lamb at 100lb I will yield roughly 50lb worth of meat in the package.

I make my grass-fed lamb available on a local basis before shipping. Subscribe below for a chance to buy my meat once my local demand is satisfied:

A lot of people ask how I cook with lamb, so I created a video with 5 American Style Recipes!

(click the photo above to watch and download the cookbook)

If you are looking to raise your own grass-fed meat sheep, check out my book for beginners: the Basics of Raising Sheep on Pasture

I TESTED LYE AS A DEWORMER FOR LIVESTOCK (vet results)

CLICK FOR MY FREE E-BOOK “13 Things You Need to Raise Sheep”

Does lye work as a natural dewormer for livestock? In this article I am going to share vet-tested results that will give you the answer. I am going to share exactly how I administered lye to act as a dewormer, the animals I ran this test on, and the detailed results from the veterinary office which reveal how effective (or not) that lye is as a natural dewormer for livestock.

Very interesting stuff is upcoming, so let’s get to it.

Premise:

If you are like me, you’ve seen or received a message about the VIRAL “Lye as a Natural Dewormer for livestock videos”: pigs, sheep, goats, cattle, chickens… The viral video claims that Lye works as a dewormer for all classes of livestock. The man who published the video says that he has been using lye as livestock dewormer for 17 years with no negative side effects observed in his animals. He cites that lye has no meat withdrawal period, and no milk withdrawal period.

Withdrawal period is a time period in which you cannot eat the meat or drink the milk of an animal that has been dewormed with chemical dewormer. Withdrawal period is necessary because chemical residuals may present themselves in either the meat or the milk directly after using chemical dewormers. The withdrawal time period ranges from 2-8 weeks depending on what kind of chemical dewormer you are using.

In watching that video, I was intrigued but skeptical. Intrigued because the animals looked healthy, skeptical because there was no real data provided that connected the health of the animals to the lye, just sort of a “I think it works and it’s what I use”. There were no fecal egg counts done to confirm that the lye was actually (the thing) reducing parasite loads.

So I decided to perform an informal research project for myself: to gather the numbers and data that was missing.

Here is exactly how it went:

But first a quick disclaimer: this Article is in no ways encouraging you to use lye as a dewormer for your livestock. Lye is caustic and may kill your animal. This is purely a research project. I am not a veterinarian, so please contact yours before giving anything to your animal as a dewormer.

Back to it:

My Test Subjects & Conditions

I used my small goat herd to test the lye as a dewormer concept. The herd is about 7 head in total: 2 kids (6 mos old) and 5 adults.

I tested this small group of goats instead of my sheep flock because (given the previous disclaimer) I was not sure if the lye would kill my animals. I can afford to lose my goats, but if I were to kill my sheep flock through this experiment I would be out a significant amount of money.

My goats are dairy goats. One of the adult nannies was pretty badly infected with parasites at the onset of this experiment (namely the barber’s pole worm), as indicated by a very severe case of bottle jaw. She was a good test subject.

To begin this research project I removed the goats from the pasture and put them in a pen.

I controlled their feed 100%: giving them a 50-50 ration of all stock feed pellets and alfalfa pellets. I also provided bermuda hay free choice.

Now removing the goats entirely from pasture and putting them into a controlled environment for the duration of this test eliminated any external factors that would either increase or decrease their parasite counts. This gave me a crystal-clear idea of exactly what kind of impact the lye treatment did or did not have on parasite counts.

The Process (and Results):

Once I penned the goats I ran the first of 3 fecal egg counts to find out how many parasites/worms were inside these goats.

Fecal egg counts are the primary means of determining whether a deworming method is effective. You must run a fecal egg count both before and after you deworm your animal. If a given deworming method is effective, there will be a significant reduction in the egg count numbers in that second test.

To run the fecal egg count you need to take roughly 4-5 pieces of goat or sheep manure to the vet. From there, the vet will provide you with egg count on the manure samples. According to my vet, 800 eggs per gram or less is what you want to aim for in your sheep and goats. Numbers higher than this represent a pretty significant parasite infection.

I ran a fecal egg count on 2 of the 7 goats in this test group: Daisy (with the bottle jaw) and Maria.

Results from test #1 showed an egg count of:

- 5400 eggs per gram for Daisy

- 1250 eggs per gram for Maria

Which means both goats were significantly infected with the Barber’s Pole Worm – far beyond 800 epg.

After this first test I gave lye as a dewormer for the first time. I followed instructions almost exactly from that viral video for my 7 goats:

- 1 teaspoon of lye

- 2 cups water

- 2 gallons of feed

I dissolved 1 teaspoon of lye in the water, poured the water into the feed and thoroughly mixed it to where all of the feed was covered in the lye-water.

Then fed it to the goats.

Two days later I took a 2nd round of fecal samples from Daisy and Maria to the vet for the second test.

Results from test #2 showed a fecal egg count of:

- 1200 eggs per gram for Daisy (down from 5400)

- 750 eggs per gram for Maria (Down from 1250)

Now this was a significant reduction, but these numbers were still really high. As a reminder: 800 epg is about maximum in terms of healthy levels.

So at this point, I took a risk and administered a second round of lye treated feed.

The same protocol as the first time around:

- 1 teaspoon of lye

- 2 cups water

- 2 gallons of feed

2 days after that second dose I took a 3rd set of fecal samples from Daisy and Maria to the vet for a 3rd test.

The vet called with the results from that 3rd test and said: there are no worms in these samples.

I said: “What do you mean, there are always some worms, what are the numbers?”

The vet-tech said: “the numbers are so low that it’s not worth counting, but I’d say around 150epg for Daisy and 300epg for Maria”. I was floored and shocked.

Results from test #3 showed a fecal egg count of:

- 150 eggs per gram for Daisy (down from 5400)

- 300 eggs per gram for Maria (Down from 1250)

So yes, lye dewormed my goats almost completely. I observed no negative side effects despite giving the treatment twice in one week.

So what are your thoughts? Is this too risky? Have you had success using lye as a dewormer yourself? Would you use Lye to deworm your own animals? Have you encountered negative side effects in using lye as a dewormer? I am looking forward to this conversation continuing in the comments!

September 2025 Farm Update | Raising Dorper Sheep in Texas

Hi Friends,

This farm update includes some long-awaited info. My Fall Lamb and Starter Flock sale kicks off this month! More updates to follow, so be watching.

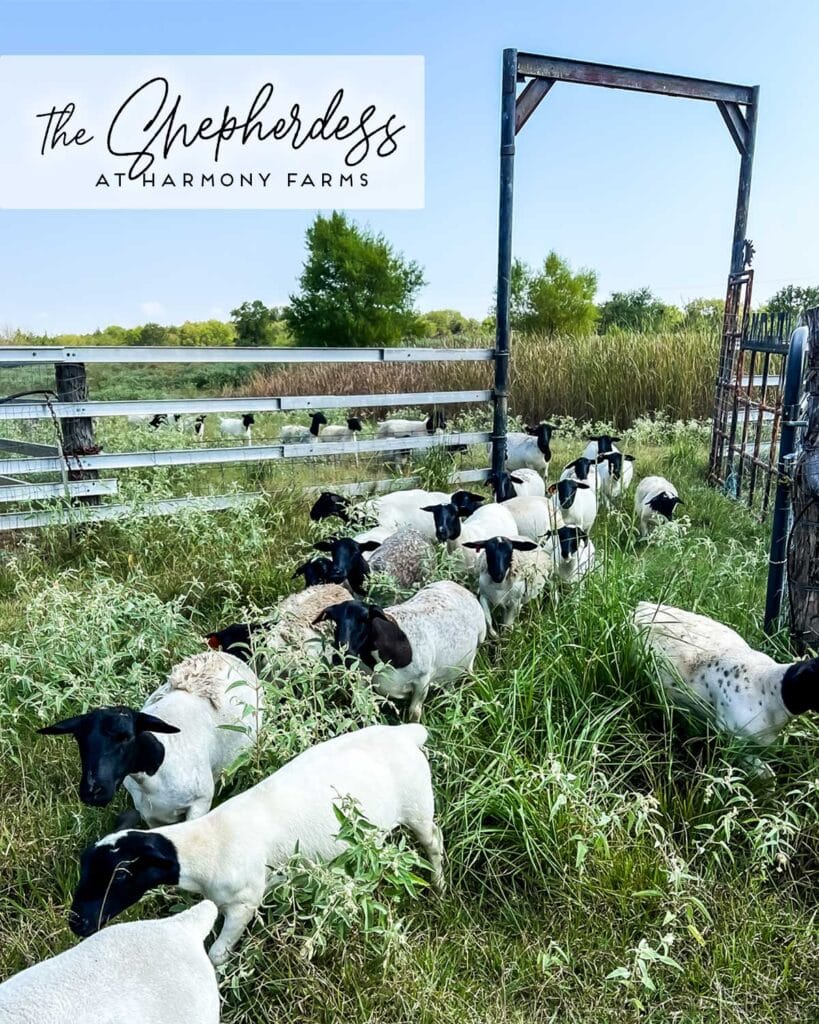

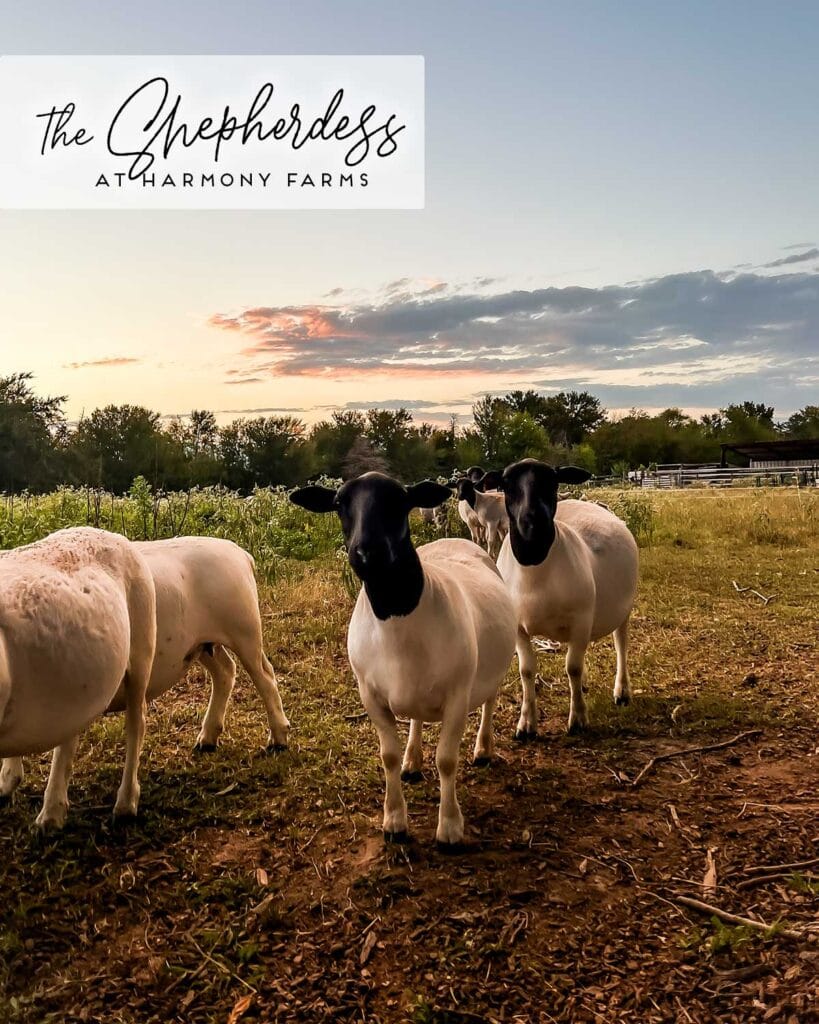

When it comes to my flock I cull for 4 characteristics: Parasite resistance, good maternal traits, hoof health, and meaty frames on pasture only.

This year a 5th trait is really emerging within the flock: uniformity. While I don’t “cull for cosmetics” it is super encouraging to see the consistency in frame (meatiness), lowline, and hair coat in nearly every sheep.

Fall lambing is underway! Due to a breeding-glitch that happened back in May, my fall lambing season is a bit smaller than usual… but the new additions are looking great!

If you have been waiting to buy lambs or a Complete Starter Flocks from my farm, be sure to be on the lookout for further updates!

I added the last of the inventory to the $10 tee sale!! We filled all the orders from the August rush, then added leftovers to the site. This is the end of my tee shirt collection until at least 2026, so jump grab yours!!

More soon,

-the Shepherdess

“The Lord is slow to anger, and great in power, and will not at all acquit the wicked:

the Lord hath his way in the whirlwind and in the storm, and the clouds are the dust of his feet.”

Nahum 1:3

HOW MUCH DO DORPER SHEEP COST?

CLICK FOR MY FREE E-BOOK “13 Things You Need to Raise Sheep”

In this article, I am going to answer a question that nobody wants to: “How much do Dorper Sheep Cost?” Now, nobody wants to answer this question because pricing for livestock fluctuates constantly. However, I am going to write this article in an effort to get you into a current price-range as well as give guidance on the various categories you’ll encounter when shopping for Dorper sheep.

I am going to give you 3 different pricing categories that purebred Dorper sheep fall into going from least to most expensive. The categories include: commercial Dorper Sheep at the Sale barn, value-added commercial sheep at private sale, and high-value registered Breeding stock.

Now something to know is that the most expensive sheep is a dead sheep, and as such I have a free EBOOK for you called “The 13 Things You Need to Raise Sheep”. It will give you a strong head start toward a healthy, profitable flock. Click this link and I’ll email it to you for free.

The first pricing category I will provide is for commercial Dorper sheep from the sale barn. A sale barn is where you will typically find sheep at the lowest cost. There are pros and cons to the sale barn: the pro is lowest cost and ability to get a large quantity of sheep. The con is that there is often not a lot of background information provided on the sheep for sale. There are no guarantees of pure bred status, it’s hard to do diligence and identify what kind of system and feed the sheep were raised on, and often Dorpers at the sale barn are mixed with other hair breeds. Unless you have a lot of experience buying from a sale barn (or help from a friend that does), you could end up with a sick sheep, mixed breed, or potentially genetics that are not suitable for your farm.

In terms of pricing, I use the San Angelo Texas livestock report and I use the “HAIR SHEEP” category of the report for an idea of current pricing for Dorper Lambs. Reports from this week show that you can purchase a 75lb “choice/prime” HAIR lamb at about $2.62 per pound. So for a 75lb lamb you can expect to pay $197 at a sale barn in Texas.

The second pricing category is purebred commercial Dorper sheep at private sale. This is the category that my sheep fall under and the category I suggest you buying from as a beginner buying sheep. Buying private sale enables you to get direct information on the type of feed the sheep receive, how much grain input, what kind of grazing system the sheep are managed under, what kind of medications the flock owner uses, and so much more. It is the best way to get a healthy sheep and the easiest way to traceback and pursue accountability and reparation should you end up with a sick sheep.

Pricing for really good quality commercial Dorper breeding stock at private sale is anywhere from $250-700/hd. That is a really wide spread that is going to be based on what kind of genetics and management the flock boasts.

I sell my breeding quality ewes and ram lambs for between $500 and $700/hd based on the really strong pasture-based genetics I have developed. My pasture raised lambs have about a 50-55% carcass yield at the butcher – meaning a hearty, meaty, low input animal. I have also bred in a lot of value-adding characteristics like parasite resistance, shedding ability, good maternal instincts, and a lot of others. This contributes to me earning top-tier for my sheep because I am breeding for a specific niche that really values those characteristics and understands that while they may pay-up for seed-stock, they are going to get paid back within their first lamb-crop (because of the quality).

But to summarize I would say that $350 per head for quality, purebred, commercial Dorper lamb at 60-80lb is not an unreasonable pricepoint at this point in time.

The third and most expensive pricing category for Dorper Sheep is registered, full-blood at private sale (or more commonly at specialty shows like the Mid-America Dorper Sheep Breeder Show). These are sheep with registration papers at the ADSBS. These papers trace the sheep’s lineage back to South Africa. Registered sheep are rarely, if ever bred for meat production. They are typically always bred for the show ring. Being show animals, they are very expensive.

Pricing will depend on the reputation of the breeder and the phenotype of the animal itself. “Typing” is done on a 1-5 scale, with 5 being the best phenotype. The price range can be anything from $800-8,000 for a breeding ewes and rams. $8k is pretty extreme but not unheard of for Dorper. This year you can expect to pay an average of $1000-1500 for a quality, registered Dorper breeding stock.

But $3,000-5,000 for a ram from one of the best breeders in the country is not uncommon. The reason is that people will pay premium for, say, a “type 5” ram so that they can breed him to a flock full of “type 3” ewes and immediately have a top-dollar, type 4-5 lamb crop that pays for the cost of the ram in the first year.

So in summary, you could be looking at pricing that is anywhere from $200-$8,000 for a quality Dorper Sheep.

If you have experience buying at a sale barn, or an experienced friend who can help you buy, you might be able to source a quality group of ewe lambs for $200 each. My preferred method is to pay around $350-500 per head at private sale to ensure I am getting good, pasture based genetics in my Dorper sheep. Finally, if you are into show animals, expect to pay a median price of $1,000 per head for Registered Dorper breeding stock.

Remember, that the most expensive sheep is a dead sheep, so be sure to download my free EBOOK on “The 13 Things You Need to Raise Sheep” for a good head-start toward a healthy flock.

Know your enemy 🪱🐑 (free class)

|

Hi friends, There is a saying that goes: “If you know your enemy and your (yes, I updated the original saying a bit, but the principle applies regardless 😄) 🪱As you raise sheep on pasture, internal parasites (worms) to be one of your biggest enemies. In fact, worms killed half of our flock in our first 2 years as beginner farmers (yep, ouch!). Today, however, worms are no longer a major issue. To keep parasites at bay, I use a combination of:

Tomorrow I am going to share all of my practices! Come with your questions because there will be LIVE Q+A at the end! Special bonus: I vet-tested the viral “Lye as Livestock Dewormer” concept and will be sharing the results from the veterinary office at the end of the livestream (as well as the potential risks of using lye as a dewormer):

Much of this info will apply to goats as well as sheep. 🐐 If you are unable to attend live, please register anyway and you will receive a replay. There is a room size limit of 150, so please log-on early to secure one of the LIVE seats. All registrants will receive a replay! To support these free monthly meetups please consider one (or both) of the following:

I look forward to seeing you tomorrow (7pm CST)! -the Shepherdess “The earth is the LORD’S, and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein.” Psalm 24:1

*DISCLAIMER: I am not a veterinary professional. Please do not attend this meetup in search of (or to supplement) professional veterinary advice. I will be sharing based on experience from my own farm. |

🥳LIVE NOW!! (bonus for first 10)

|

🎉📚 MY BOOK’S 2nd BIRTHDAY EVENT IS LIVE!! (Shepherdess Dorpers Ceramic Mug to the first 10 book orders, and the $30k Side Hustle Planner comes WITH EVERY BOOK*!!)

Birthday week bonuses:🎉 (Bonuses start in for all orders after 8am CST on 8/15 and are granted on a first-come basis)

Keep in mind, the first 10 orders will receive all of the above in ONE MEGA BUNDLE… there are some serious perks this year!!!🎉🎉🎉

Already own the book, but want access to the $30k Side Hustle Planner?

|

| LEAVE a Review |

*Offer runs while supplies last or until 8/21.

For a look at how the book came together, watch this video!

The Basics of Raising Sheep Book is 100% printed and constructed in the USA!⬇️⬇️

|

|

-the Shepherdess

“So then neither is he that planteth any thing, neither he that watereth; but God that giveth the increase.” 1 Cor. 3:7

[Business BOOTCAMP] Monday Briefing

|

Hi Friends, It is time for the Monday Briefing! I am pretty excited about this month’s 🎙️COMPLETION PRIZE, so scroll for info!! ASSIGNMENT SUMMARY: We are in week number 1 of Month 5! In our final months of Bootcamp I am going to be unpacking my entire Content Marketing Strategy for you. This week, I am addressing the importance of a Service-based Mindset in Marketing: Lesson 1 in Month 5: Marketing Mindset & Messaging

(be sure you are logged in when clicking this button or you will see “not enrolled”) Good Marketing is founded on 3 principles, primarily:

Principle #3 has been the most important for my business: serve before you sell. In my first year of marketing, I was giving my customer base a lot more than I was receiving. I “gave” in 3 primary ways:

These were ways of giving that were tied into my Lead Capture strategy (the one that I taught you in Phase 2), so it was a win-win… but the premise is the same: I had to give before I could ask… and it paid off… By the time I had products ready to sell, I had an email list of people that I had been serving (through a free resource, videos about my flock, and educational blog post)… …and these people were warmed up ready to buy. This is also why I suggest that you start marketing before your product is ready to sell. The warm-up process takes time :). 🌱 What a soil base and a customer base have in common… As regenerative farmers, we know that a soil base usually requires that we give it something before we pull a harvest out of it. The same principle applies with to a customer base. Constantly taking is never a winning strategy. The size of our harvest typically relies on the strength of our input… More on a how to establish a Service Based Mindset in Marketing in Assignment 1:

COMMUNITY UPDATES:PODCAST IS UPDATED! I have updated the member-only podcast with:

Here is how to add the Member-Only Podcast to your Podcast Library:

COMPLETION PRIZES for Month 5: All students to complete this month’s assignments will be entered into a drawing for one RODE NT-USB Mini USB PODCASTING Microphone. This connects to your laptop or tablet and is ideal for Podcasting and recording audio narration for YouTube videos. As a reminder: completion prizes are a fun incentive to stay focused, not an encouragement to rush :). Keep at it, slow and steady! -the Shepherdess “And let the beauty of the LORD our God be upon us: And establish thou the work of our hands upon us; Yea, the work of our hands establish thou it.” Psalm 90:17 Earnings Disclaimer: Every effort is made to equip you with the tools and strategies you need to reach specific financial goals. However, there is no guarantee that you will earn money using the classes I provide for you. God alone gives the increase and will dictate whether you are profitable or not. This education comes with no warranties or guarantees. By participating you agree that you understand this earnings disclaimer. |

HOW TO RAISE DAIRY SHEEP (for beginners) Including Where to Buy Dairy Sheep

DOWNLOAD MY DAIRY SHEEP FACT SHEET HERE!

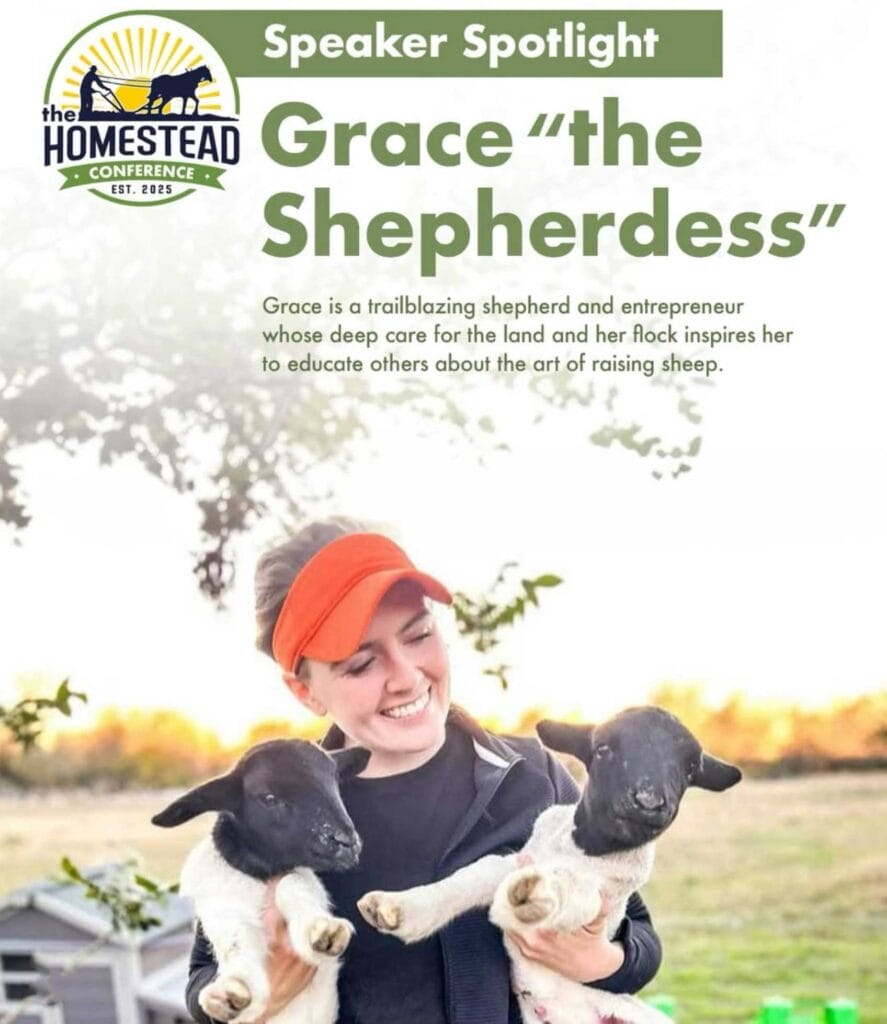

If you are considering Dairy sheep for your homestead, this video is for you! Lydia At Harmony Heritage has raised dairy sheep in Washington State for 22 years – since the age of 9 years old.

In this interview we discuss:

- The best dairy sheep breeds and cross breeds for hardiness.

- How to mitigate (and even eliminate) mastitis in your dairy sheep flocks

- Where to find quality dairy sheep to buy (and how much you might pay)

And MORE.

HOW TO RAISE DAIRY SHEEP

the Shepherdess: I am so thrilled today to be talking with Lydia of Harmony Heritage Farm. Lydia, give us a little bit of an overview of Harmony Heritage Farm—where you’re at, what you’re farming, and when it all started.

Lydia: We are living on about 48 acres of totally raw land right now that we purchased in 2018. It used to belong to my husband’s family back in the fifties.

They had quite a few acres up here in Mossy Rock in the hills. I think in the late 1800s is when they first kind of settled here. There’s a lot of history there. It was really a huge opportunity for us to be able to purchase that.

So we have that for ourselves, and we’re just slowly but surely working on it. It was really super rough property because it was logged in the fifties, and all the stumps were still there, kind of rotting, and lots of blackberries—just rough ground. [00:01:00] So a lot of work has gone into that. We are in Washington state.

the Shepherdess: And what is the climate like for you? Do you have snow? Is it temperate?

Lydia: We’re almost more coastal, so we get a lot of rain.

Normally. This has been a really super dry year, so we’re kind of a little nervous as far as grass and how much hay we’re going to have and all that.

the Shepherdess: So when did you decide to go for sheep?

Lydia: I was thinking about that. It’s just been kind of a natural love that was instilled in me, I think, at a very early age. My mom decorated my nursery with Psalm 23 things, so I had sheep in the room everywhere.

Finally, we moved out here to Washington when I was seven or eight, and my parents said, “It’s time. We need to get some sheep.” So my mom ended up [00:02:00] calling around to like 10 or 15 sheep farmers in the area.

We had this directory of sheep producers, and she said, “Okay, well, whoever calls us back first, we’ll find a sheep for you.” As it went, we only had one person respond—and it was a dairy sheep farm that’s about 30 minutes from us.

So I didn’t even really intend to get dairy sheep at that point. I was just like, “Any sheep will do, I don’t care.” I think I bought a sheep and my sister bought a sheep.

the Shepherdess: Wow. And so you’ve been growing it since then, or was it kind of an off-again, on-again relationship?

Lydia: I have not had one year since I was nine that I haven’t had a sheep.

I think I’ve moved like five or six times, and God has always provided some way for me to keep sheep in my life. One time I even had some friends just keep my sheep for me.

‘Cause I was like, I’m not sure [00:03:00] if we’re going to be able to buy property, but I don’t want to lose my genetics because I’ve worked so hard for what I have, and I didn’t want to lose that line of sheep. So they offered to keep them for me for a season and just gave them back to me after that.

I’m just so grateful. I really think it’s something God has allowed me.

the Shepherdess: Amen.

What breed of sheep are you running?

Lydia: So I have primarily East Friesian crosses. I’m sure you’ve heard about East Friesians. They’re the top dairy breed in the U.S., and they are actually always a mix. We don’t have any purebreds here in the States. They’re normally like East Friesian— I think it’s pronounced Lacaune.

It’s a French breed. Those were the first two dairy breeds that were brought to the United States.

the Shepherdess: How do you spell the last one?

Lydia: I have it on here as L-A-C-A-U-N-E. That’s a breed I really love—that Lacaune, they call it. East Friesians—I have a love-hate relationship with East Friesians because they are kind of your Holstein. They were bred for production, so they tend to be really difficult to keep.

They’re not as hardy, but they produce a ton of milk. So that’s kind of their main claim to fame.

the Shepherdess: Being…

Lydia: Huge producers. But some of the things I was seeing early on with the East Friesians is they’re bred for very short-term, heavy production. So you can expect two to maybe four or five good years of milking and then they get Mastitis. So I early on started breeding in some of the hardier, better-built sheep like Border Leicester. And Lacaune is another Canadian dairy [00:05:00] breed that I am just a huge fan of.

I’m trying to think—my initial, very first sheep that I got was a Lacaune. I just love them because they’re very, very hardy. They have those long—I’m sure you probably know, in your breeding program—you want long bodies, long deep bodies so they can carry lambs well and not have prolapse issues.

And it just gives you a little more meat. So yeah, Lacaune are really valuable for that reason. I incorporated Finns maybe six or seven years ago. I love them for their wool quality and quantity, as well as their lamb production. They tend to have huge litters, which is something that appealed to me.

It’s fun to have lots of babies. The other thing is it does aid in milk production too.

So I’ve heard that the number of lambs [00:06:00] your ewe is carrying affects her milk production—she automatically knows she’s going to need more milk to support them. So I started crossing in some purebred Finns. I had a flock of dairy sheep and then a flock of purebred Finns.

And I decided I really don’t like purebred Finns because—at least in the States—they do tend to be a little smaller and a little bit inbred. There’s not a ton out there. So they were really hard to keep—hard to keep weight on them, wormy all the time.

But crossed with the hardier breeds and the dairy sheep? They’re amazing. So in my breeding program, I like to keep the percentage at 50% or less Finn.

the Shepherdess: So if you could say three goals that you breed for, what are the three things that you breed for in a ewe—if it’s only three?

Lydia: So for the dairy sheep, my first goal was just personality and temperament, which is pretty easy with dairy sheep.

They’re bred for that, so they tend to be more calm and easy to work with for the most part. But there is nothing worse than fighting with a sheep that doesn’t want to be milked. So that’s number one: temperament and personality.

Number two is udder conformation. For me—because I hand-milk all of my sheep—it’s really important to have a good teat structure and udder conformation. And in dairy sheep, they’re not as good as dairy goats yet.

In the States, that’s something we’re really working toward—having udders that are really easy to milk and that won’t create problems like mastitis. That’s been my main goal: to have sheep that have an udder that doesn’t hang below the hocks, because we have really brushy ground up here and they tend to get [00:08:00] mastitis really easily if they’re very heavy and hanging.

And that’s really common with dairy sheep—to have poor udder conformation. So I go more for the conformation than production. I’m not as concerned about how much they’re giving me in a year as I am about…

the Shepherdess: Right, because that will lend to longevity. She’ll be with you longer. So in the long run, she’ll probably produce as much as that one that gives like six gallons, you know, a week.

Lydia: Absolutely. I really, really strongly believe that. And it’s heartbreaking to lose them—especially for the smaller people like us, homestead-type operations, where you’re milking them every day and you’re attached to them and you love them.

And if they’re dying every two years—that’s not fun. And dealing with mastitis is the worst thing to ever have to deal with.

the Shepherdess: What are some [00:09:00] things that you would guide people to—some ways to treat mastitis? I had a couple cases in my flock this past year.

How would you treat it, and what has been most effective for you?

Lydia: Yeah. Early on, someone recommended the cow mastitis treatment—the intramammary ones. There’s “Today” and “Tomorrow.”

And I will usually treat them with “Today.” If it’s really bad… If it’s not that bad—normally these days I hardly ever get it, thankfully—I don’t have to deal with it much anymore.

But I do get a lot of—what do you call it? It’s when they first lamb and the udder is pretty firm and hard and hot. A lot of times you can use essential oils and compresses and just a lot of massaging.

And if you can leave the lambs on them or allow a lamb to nurse continually, that really helps too.

the Shepherdess: That’s really good.

All right, so what is a general milk yield? What would you consider, at your farm, a good-producing [00:10:00] sheep?

Lydia: So we breed at like eight or nine months of age, so they will lamb their first year. And that first year you really don’t get much—you can’t expect much out of them, ’cause they’re still babies. They’re kind of growing themselves.

And then to also have a lamb that they’re carrying—usually one or two lambs—that’s just a lot for them. So normally I tell people between one and two cups per milking their first year. So you may get two cups a day, or you might get four, depending on the ewe.

And then the next year you can expect that to double. I would say their golden years are kind of two to six years old, maybe eight years old. And my really good producers give me a gallon a day plus. My decent milkers are around three [00:11:00] quarters of a gallon a day.

The first month after lambing, all of that milk goes to the lambs. I separate it for 24 hours, and then I just feed all that milk back to the lambs.

Then after a month, when they’re weaned, we’re able to keep that for ourselves. I continue to milk until about July. I start to taper them off a little bit—first I start off with once-a-day milking, then I taper off to every other day.

By the end of August, I have them pretty well dried up for breeding and all the pre-lambing things that need to happen—worming and selenium.

the Shepherdess: What are the feed rations in order to get that kind of a yield?

Lydia: That’s a really, really good question because production depends so much on what they’re eating—and not as much on genetics. We have a ton of green grass here, especially in the spring and usually into summer. We’re very blessed that way. So I don’t supplement them with any grain after lambing, except maybe a handful.

Before lambing, I try really hard not to grain them at all. I know it’s really hard on their stomachs, and they do much better if you stick with alfalfa and grass hay. I’ve had years where I tried graining more—using this alfalfa haylage called Chaffhaye. I don’t know if you have it down there, but it’s great for dairy sheep because they need the water content and the high calcium from the alfalfa.

But dry alfalfa hay gets wasted a lot, so I love the Chaffhaye. Still, one year I tried graining them harder due to poor pasture, and I had a lot of bloat. It was awful. I had a little Mexican friend come butcher some sheep for me and he asked, “Why are you giving them grain? They don’t need grain—they have pasture.” And I was like, Oh, okay.

the Shepherdess: So you’re getting that kind of yield on pasture only?

Lydia: Yeah. It’s really pretty awesome.

the Shepherdess: Let’s talk about supplemental minerals. Dairy animals tend to be a little more sensitive. What should people prepare for?

Lydia: Where I live, selenium is a big issue. Even the mineral mixes don’t have enough. In my earlier years, I had problems with white muscle disease and lambs failing to thrive. So now I always give a Bo-Se shot right before breeding, and then I give them the paste a couple of weeks before lambing as a little boost. I also vaccinate the lambs with Bo-Se at weaning.

the Shepherdess: Do you ever struggle with hypocalcemia?

Lydia: Yes! I have a tip for that—Tums. Just over-the-counter Tums. It’s calcium, and the sheep love it. They’ll gobble it out of your hand. I offer it to my high-producing ewes and most of the time they’ll eat four or five tabs a day. I think it really helps. That, plus giving them alfalfa in the last months before lambing, works great.

the Shepherdess: When my sheep are lactating, parasites become a big struggle. Is that the same with dairy sheep?

Lydia: It can be. But I’ve been able to avoid chemical dewormers except right before breeding. I use Valbazen around the first week of August. We rotate pastures every three days, so that helps a lot. I’ve tried natural methods like garlic and Shaklee Basic H, but I’m not sure how effective they were. We do have some liver fluke issues here, so I rely on Valbazen. But during milking, I usually don’t have to deworm at all.

the Shepherdess: Do you lamb on pasture or in a facility?

Lydia: We usually lamb in January and February, sometimes March for the younger ewes. We keep the sheep in a greenhouse over winter and lamb them out there. Once we start rotating pastures in March, lambing happens on pasture. But dairy lambs often need more attention, especially when there are three or four in a litter. I prefer to have them in lambing pens. I keep them there for 48 hours to make sure they get all their colostrum and a little selenium shot.

the Shepherdess: Your sheep are incredibly prolific. Didn’t you have a 300% lambing rate one year?

Lydia: Yeah, I had 10 ewes lamb and ended up with 33 lambs. They’re amazing.

the Shepherdess: For someone new, what are the biggest challenges with dairy sheep?

Lydia: Start with good stock from a reliable source. There’s a huge range in milk production and hardiness among dairy sheep. I was lucky to live near a dairy that always picked the best sheep for me—best for hand milking, best udders. Commercial dairies often focus only on volume, which might not suit a small homestead. Also, support is important. Books are great, but being able to talk to people helps a lot.

We have a Facebook group called Homestead Dairy Sheep—there are about 5,000 people now. My friends Joy (in California) and Josh (a dairy farmer in Nevada) helped start it. People can post questions, and we’ve got members with 20–40 years of experience who share great advice—even on cheese making.

the Shepherdess: What’s a reasonable price range for a good dairy ewe?

Lydia: I sell my ewe lambs for $500. Those are first-year lambs ready to breed in the fall. My best in-milk ewes go for $1,000. In general, expect to pay $800–$1,200 for a proven ewe with a great udder. Lambs should range from $300 to $500. If you see dairy sheep for $200–$300, be cautious—that’s low.

the Shepherdess: Do you use the milk for personal consumption or products?

Lydia: Both! We drink it and make a lot of cheese—mostly a simple, spreadable chèvre that we eat all summer. We also make ice cream and, occasionally, butter. Butter is tricky because the cream takes a while to rise, but it’s phenomenal.

the Shepherdess: Do you prefer sheep milk over goat milk?

Lydia: Absolutely. I’m not a fan of goat milk at all. But with sheep, what they eat really affects the flavor. I stopped giving alfalfa pellets while milking because it gave the milk a sour, almost fishy taste. Once I quit those, the milk was sweet and amazing. The brand may have mattered. I’m still looking for a good barley/oats/pea mix.

the Shepherdess: You’ve put a lot into your genetics. How can people get in touch with you if they’re looking to start their own dairy flock?

Lydia: Email is best:

📧 [email protected]

Or text me at:

📱 360-880-6181

You can also connect with me on Instagram and Facebook at Harmony Heritage Farm. I do ship sheep across the country. The last ones went to Oklahoma—it cost about $500 per head for shipping. I work with reputable shippers who use clean, safe, compartmentalized trailers. I wait until the lambs are a bit older so they travel strong and healthy. I’ve shipped to Arizona, California, Nevada, and now Oklahoma.

the Shepherdess: That’s a great price. Do you have any availability right now?

Lydia: I do! I have about 10 ewe lambs and 9 or 10 ram lambs still available as of this recording.

the Shepherdess: Do you have a website where people can learn more?

Lydia: Yes! Visit harmonyheritagefarm.com.

There’s an application form on the “Dairy Sheep for Sale” page where you can share about your needs, what you’re looking for, and your family setup. I also post pictures of most of the available sheep, and you can reference them by tag number when contacting me.

$100K PER ACRE MARKET GARDEN BUSINESS (full interview)

Earning $100k per acre farming and direct marketing organic vegetables: almost unbelievable but true and Robert Wagner of Wagner Farms is here to tell us exactly how, including:

- How he started his vegetable farm in 2020 and grew QUICKLY.

- His unique business model that enables him to serve 156 customers every week WITHOUT A FARMER’S MARKET.

- How he organizes his systems to produce almost 60,000 LBS worth of produce on a single acre.

- And MORE

Specific topics are time stamped below and for a printable cheat sheet featuring the top 10 takeaways from today’s discussion on EARNING $100K PER ACRE FARMING, click on the link above and I will email it directly to you.

ROB’S WEBSITE: theWegenerFarm.com

The Shepherdess:

Today we’re talking with Rob and his family, who are working with just 1.5 acres to produce around 60,000 pounds of food annually—and serve 156 CSA customers. We’re going to dive into how they do it.

First, the goal of the Virtual Small Farmer Meetup is to connect small farmers from across the nation—and around the world—to share skills, resources, and encouragement. If you’re here with questions, there are a ton of people ready to help.

Rob, can you tell us where you’re located?

Robert Wegener:

Sure. We’re in Fenton, Michigan.

One interesting thing about our location is that we’re on one of the only hills in the area, which creates a unique little microclimate. So even though we’re in the middle of Michigan, we’re really in Zone 6B. We can stretch the season a little more than you could just a mile in any direction from here.

The Shepherdess:

Wow, that’s neat. Alright, everyone, warm up the comments and let us know where you’re tuning in from tonight. Where in the world are you, and what are you farming? If it’s just hopes and dreams right now, go ahead and share that too—it counts!

I’m here in Northeast Texas, farming primarily Dorper sheep. Occasionally, I’ll raise a beef steer or two, and my sister runs laying hens. Rob, give us a rundown of what you’re raising on your farm.

Robert Wegener:

We’re primarily an organic vegetable farm. We got our USDA certification about three years ago.

We currently have around 270 laying hens, and by summer we’ll grow the flock to nearly 500 to supply our CSA. We also raise broilers and, for the first time this year, we’ll be doing some turkeys. And—if I learn enough from the Shepherdess—we may try our hand at sheep!

The Shepherdess:

That sounds like a solid plan. Let’s dive in.

When did you start your farm?

Robert Wegener:

We bought the farm in 2020. Our first CSA was in 2021 with 10 friends we pretty much cornered into saying yes. That first season was all about seeing if we could actually grow anything.

Now we’re five years in. Last year—year four—we had 120 shares, serving about 156 families (some folks had half shares). We also serve a few hundred families through our farmers market and our farm stand, which I jokingly call my “vegetable vending machine” at the end of our driveway.

It’s been pretty astronomical growth. This year, we’re actually dialing it back a bit—we got a little ahead of our systems last year. Now it’s time to make the farm more efficient and profitable so it’s sustainable long-term.

The Shepherdess:

So 156 CSA customers—are you looking to expand past the 1.5 acres?

Robert Wegener:

Actually, I’d like to go smaller.

If you’ve ever heard of Conor Crickmore in upstate New York—he’s farming less than an acre and making four times the revenue we are on 1.5 acres. This market gardening thing really comes down to systems, efficiency, and how intensely you can use your space.

So I don’t see us expanding our vegetable acreage. I would love more land for animals though—like I said, I’m interested in sheep—but that would mean acquiring a separate property.

The Shepherdess:

And is 1.5 acres your total land base?

Robert Wegener:

Yes, though about 10,000 square feet of that is under plastic—you can see one of our caterpillar tunnels in the background.

The Shepherdess:

Let’s talk business model. Folks are already asking: What is a CSA?

Robert Wegener:

Glad you asked—I get excited about this.

CSA stands for Community Supported Agriculture. The model came from a need to match farm revenue with farm expenses. It’s basically a subscription: customers pay at the start of the season, and that gives me the capital I need to grow the food. In return, they get fresh vegetables and eggs all season long.

But the best part is the community. Our pickup points have become places where people swap recipes, canned goods—you name it. It builds a real connection and keeps folks coming back year after year.

The Shepherdess:

That’s great. How often do customers receive their shares?

Robert Wegener:

We offer four products—two full shares (weekly), and two half shares (every other week). The half shares allow us to offer a lower-cost option while still keeping production even. Two half shares staggered across weeks look just like one full share from a production standpoint.

The Shepherdess:

You mentioned earlier that predictability is a big benefit. Why did you choose CSA over just going all-in at the farmers market?

Robert Wegener:

Predictability is key. I know at the start of the season exactly what I need to grow. I tell people it’s like writing a symphony for 50 instruments—we grow 50 kinds of vegetables. You need to know when to seed, transplant, harvest, and pack.

We grow extras for the market and the farm stand, but the CSA helps us plan. It also lets us grow things we love but couldn’t sell easily at market. We can put something unique in the box, share a recipe, and create excitement.

The Shepherdess:

It sounds like you’ve built a whole system. Did you have a background in farming before this?

Robert Wegener:

At age 12, I was driving a big old tractor—an Oliver 4-270. I worked on my uncles’ farms until I was about 17. Unfortunately, they didn’t adjust to the changing agricultural landscape. They never shifted to direct-to-consumer or higher-margin models, and those farms eventually disappeared.

At the time, being a farmer wasn’t exactly “cool.” It was what you did if you couldn’t figure out anything else. But now, after 30 years in corporate America, I want to be a farmer. I’m stepping away from a corporate career to do what I started at 12.

The Shepherdess:

That’s a powerful full-circle moment. And CSA is such a direct-to-consumer model, too. I recently interviewed Luke Groce, and he started with vegetables in a CSA like you, then added meat. The beauty was that he already had the customer base in place.

You’re also certified organic. Was that something you started with or added later?

Robert Wegener:

We certified halfway through our second year. The process isn’t easy, especially for market gardens like ours with high diversity. But it was worth it—the value of that certification in the market is significant.

Transparency is what really matters. Not everyone can tour the farm, so certification gives customers peace of mind. But yes—it’s a lot of paperwork. We have to track everything from seed to sale, even on a single head of lettuce.

Luckily, I’m decent with Excel and built tools to help us stay organized. We also use Slack with our crew—it creates a great audit trail for inspectors.

The Shepherdess:

That’s brilliant. You’re adapting business tech tools to the farm.

A question came in: Can you break down your CSA pricing? Have you had to raise prices, and can the market support that?

Robert Wegener:

We’ve raised prices every year. We also have a “founder share” with a discount for our original customers—it’s a thank-you for their loyalty.

For 2025, our full share with weekly vegetables and a dozen eggs for 18 weeks is $845. Pay by check and you get a discount (saves us credit card fees). The half share with eggs is about $430. We also offer both without eggs at a lower price.

We spent a lot on marketing last year. This year, we’re charging 16% more—but doing much less marketing. That’s the power of building a brand and tapping into growing demand for honest food.

The Shepherdess:

That’s a great segue. After those first 10 friends, how did you scale to 156 CSA members?

Robert Wegener:

Lots of social media, word of mouth, and some partnerships with local businesses. Social media has been a powerful tool.

The Shepherdess:

Someone’s asking where you got your caterpillar tunnel.

Robert Wegener:

Farmer’s Friend. Best deal going. They’ll ship you a full kit on a pallet with everything you need. If you want to save even more, buy it without hardware and source locally.

We also have two big high tunnels—120′ x 32’—with lots of automation. Those came from Nifty Hoops, a local company here in Michigan. They built the high tunnels; I built the cat tunnels.

The Shepherdess:

What do your hen runs look like?

Robert Wegener:

That’s a bit of redneck engineering! One’s built on a hay wagon with wire and rollout nesting boxes to keep the eggs clean. Another is on a roadworthy wagon—same setup. We also have one on skids built by the Amish. We move them to fresh grass as much as possible.

We use nipple waterers and 55-gallon barrel feeders with ports around the edges. We can load them up once a week and avoid daily chores.

The Shepherdess:

Ariel asks: how do you plan your plantings to match the number of customers?

Robert Wegener:

Trade secret! Just kidding.

I’ve built an Excel model over the years. Based on past data, I know yields per bed-foot. For example, I know a 100-foot bed of bok choy will yield X pounds based on prior seasons.

For season-long crops like eggplants or peppers, we plant based on experience. For potatoes? I plant as many as I can find space for. They’re not profitable in a market garden—but they’re just so cool to grow. Our customers love them.

The Shepherdess:

So they take too much space and time?

Robert Wegener:

Exactly. Potatoes occupy ground all season, while bok choy turns over in 30 days. Same space, way more yield.

The Shepherdess:

Out of curiosity, what’s your day job?

Robert Wegener:

I’m a financial services executive—with an MBA from the University of Michigan and an econ degree from a small liberal arts college. Definitely one of those “overeducated” types. But now I just want to farm.

“He who is faithful in what is least is faithful also in much; and he who is unjust in what is least is unjust also in much.”

Luke 16:10

May 2025 Farm Update

Looking for Dorper Sheep for sale? Join my waitlist here:

Hi friends,

This month definitely had some extreme highs and lows… it’s been a rough week and I’m going to share about it in this update.😔

Good News:

Let’s start with the good news: all 2025 lambs have been safely delivered to their new owners (with a few more stashed in freezer camp)! It was a huge pleasure to meet so many of you and put these lambs into good hands.

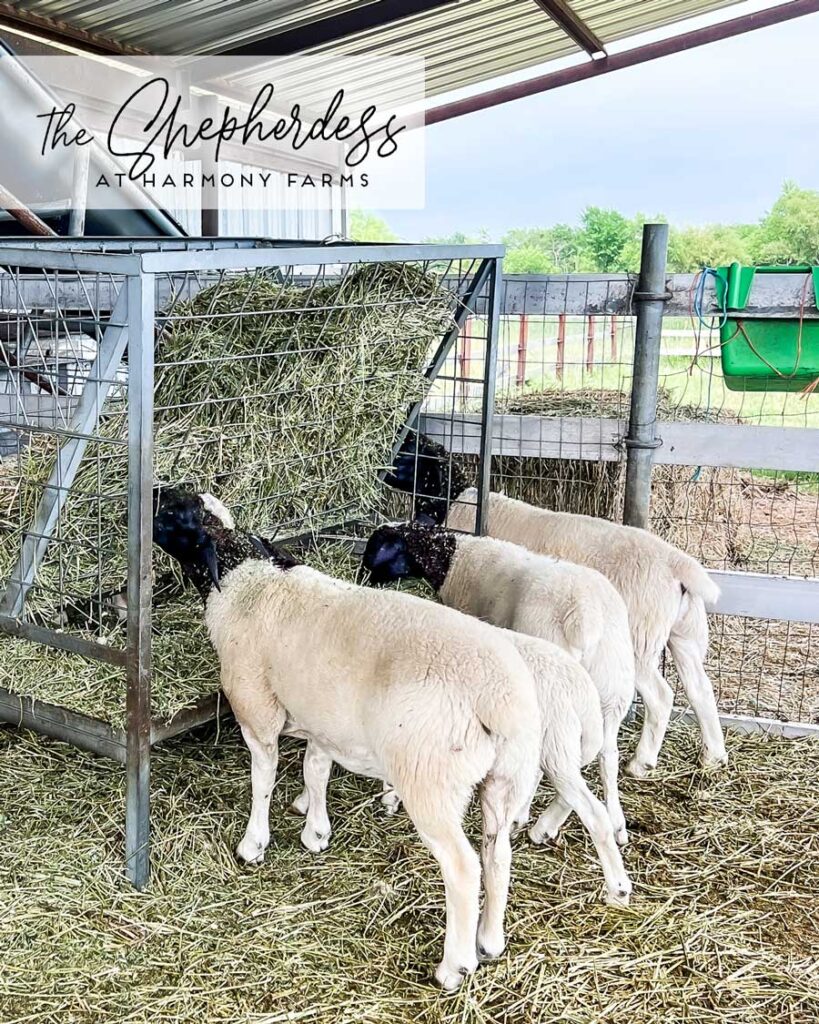

The last handful of early-spring lambs are weaned and looking great! As always, my lambs are weaned into a clean pen (for 2 weeks) and fed alfalfa hay before rejoining the flock. This allows the ewes to dry off and the lambs to adjust to all forage in a controlled environment with quality feed.

Bad News:

Now I guess I’ll get to the sad news. Back in January my rams broke out of their “seasonal confinement” and spent enough time with the flock to breed a few ewes. Lambs born in May and June always fail to thrive on pasture (parasites), so I avoid lambing in these months… however 5 sweet surprises popped up on pasture this month – and I was in love. 🥰

Unfortunately, however, last week we had the first predator attack in 3 years. A pack of dogs or coyote (we have both) came through and took out all of the newborn lambs overnight.

One lamb was left half eaten, another found dead, and the other three were completely missing.

The details:

This instance was honestly a logistical error on my part. When I have lambing ewes I keep them as close to the house as possible and make sure they are near the enclosure in case I need to shut them up overnight. Because this was not a regular lambing group I dropped protocol and maintained my regular rotation.

In May and June I graze the flock at the far end of my 30 acres, which is near the edge of the woods: the very worst spot for grazing when tiny lambs are in the mix.

About a day before the attack, one of the ewes gave birth at the edge of the woods. Presumably, the after-birth from that delivery encouraged predators even further.

It was a pretty sickening experience, but honestly could have been a lot worse. I had just weaned my spring lambs into a safe pen and the lambs that I sold were safely with their new owners.

For those who will likely ask if I have a Livestock Guardian Dog: we do have a large Pyrenees mix that roams the majority of our 30 acres. To her credit she was trying to get our attention the night of the attack. I have not had success bonding a formal LGD to the flock: my last Pyrenees was a wanderer and we lost him to highway traffic.

I hope that sharing some of these details will help you! Maybe you can use it to adjust or add to your own system to avoid similar losses.

In all, it was really sad, but thankfully (because they were surprises) I was not banking on these lambs for income. The Lord was merciful to cut my losses, remind me of why certain protocol is important, and give a dose of humility – which is always a good thing to grow in.

I will close on a positive note! The 3rd printing of my book, the Basics of Raising Sheep on Pasture, was delivered. THANK YOU for your supporting my self-published (not on Amazon) book. A special thanks to Redmond Agriculture and Lakeland Farm and Ranch for helping with the printing costs on this 3rd edition.

-the Shepherdess

P.S. Submission deadline for the Dorper Dream Flock Giveaway has been extended to June 15th. Read about how you can apply for the starter flock HERE!

“And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are the called according to his purpose.”

Romans 8:28

NATURAL BEEKEEPING FOR BEGINNERS (with Dr. Leo Sharashkin)

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE NATURAL BEEKEEPING FACT SHEET (PDF)

Did you know you can start a beehive without buying a single bee? Dr. Leo Sharashkin of Horizontal Hive is going to give a beginner level explanation of how to raise bees naturally: no chemicals, no sugar feeding, no antibiotics!

Beginner Guide to Raising Bees Naturally (no chemicals)

the Shepherdess:

Dr. Leo Sharashkin, thank you for joining us! Go ahead and give us some background. When did you start beekeeping?

Dr. Leo Sharashkin:

Thank you, Grace. From as far back as I can remember, even as a small child. My uncle was a beekeeper in Russia—he started in 1972, before I was even born. My favorite vacations were summers spent in his village, about 200 miles east of Moscow. He kept both vertical and horizontal hives.

As a kid, I was more into playing than watching bees—but I noticed something. The older my uncle got (he’s 86 now and still keeping bees), the fewer vertical hives he had. That’s because they require strength—lifting 70-pound boxes isn’t easy. But he could keep working his horizontal hives without hurting his back.

When we came to the U.S., I just wanted to have bees for our family. We weren’t finding honey like my uncle’s—rich, full of pollen and bee bread. If we have time, we can talk about how hive management changes the quality of honey. But I’ll just say: most people here don’t even know what bee bread is. It’s fermented pollen inside the comb, and it’s a superfood.

So we started keeping bees for our own use. And I’ve never bought a single bee. We went from zero to 50 hives just by catching swarms.

the Shepherdess:

Wait, all 50 hives came from swarms?

Dr. Leo Sharashkin:

Yes! Just using boxes like this one (holds up a small hive box). You hang it in a tree in spring, and bees move in—just like birds into birdhouses. Everyone knows how birdhouses work, but for some reason we’ve forgotten the same applies to bees. Put a box out, and bees will come.

Here in the Ozarks—zone 6—this is the time of year I hang out my swarm traps. Pioneers knew this, because they didn’t have FedEx to ship bees from Florida. But that traditional knowledge got lost when bees became something you could buy.

People think you have to buy bees, but you don’t. The best things in life come free—why should bees be an exception?

the Shepherdess:

That’s incredible.

Dr. Leo Sharashkin:

And I’ve never treated them with chemicals. No sugar feeding. Everyone around me said it wouldn’t work, that my bees would die. But my survival rates are consistently higher than those who buy package bees. Their bees make a honey crop, die in winter, and then they have to buy more.

So not only is natural beekeeping more rewarding, but it also puts a smile on my face. I even translated a book from Russian that got me started—it’s called Keeping Bees with a Smile. It explains how bees live in the wild and how we can mimic that.

There’s a robust population of wild honeybees surviving without treatments—even with all the parasites and pesticides out there. If wild bees can make it, so can ours—if we use hardy stock and work with nature instead of against it.

Interest in this has exploded. We can barely keep up—just today, we shipped 12 pallets of orders. Too much for a regular FedEx truck—they had to send a 26-foot box truck!

I do sell honey, and it’s premium stuff. But the real joy is when people buy equipment or even just download my free plans, then send me pictures of their kids eating honeycomb fresh from their hive.

The Shepherdess:

Scott in the comments says:

“Thanks to Dr. Leo’s free plans at HorizontalHive.com, I built 10 swarm traps this winter. Thank you!”

Now for the first question of the night:

“Have you heard of Flow Hives, and what do you think of them?”

Dr. Leo Sharashkin:

Yes, Flow Hives are essentially regular vertical hives—except the section where bees store honey is replaced with a special honeycomb made out of plastic.

This is not the direction I would go. First, it’s a fairly expensive setup. Second, I don’t even package my honey in plastic—only in high-quality glass jars. Over time, plastic can leach into honey, which is why in many countries, honey is never stored or sold in plastic—only glass. I wouldn’t be able to sell my honey for $50 a pound if I kept bees on plastic comb.

There’s so much that goes into doing it right, and the first step is to keep it simple and close to nature. Bees build honeycomb from wax and propolis—the resins they collect from trees. This natural comb has antibacterial properties and helps keep the hive healthy. Replace it with plastic, and you lose those benefits. Then you have to start medicating your bees to make up for it.

Bees are part of a complex ecosystem. The farther you go from their natural setup—using plastic comb, plastic foundation, or poorly insulated boxes—the more work you create for yourself to compensate for what you’ve broken. Bees in the wild live in tree hollows with excellent insulation. That’s what they’re adapted to.

Also, bees modify natural honeycomb to suit their needs—they’ll chew holes for ventilation or traffic. They can’t do that with plastic.

So, I don’t use Flow Hives. But if you have good experiences with them, please send me pictures and your story. I’d love to learn more. For me, I keep it simple and natural.

The Shepherdess:

Great. We’ll keep laying some groundwork before we get to the big questions—like how to attract bees.

Here’s a simple one:

“What are the advantages of keeping a hive on the homestead?”

Dr. Leo Sharashkin:

First and foremost, you get honey you know is real. Not many people realize this, but in America, 60–70% of honey consumed is imported, including from China—the largest honey producer in the world. I almost said “manufacturer,” because some of it isn’t even made by bees. It’s synthetic honey, formulated in labs to taste like honey.

In Europe, they say every fifth jar of honey is fake. And that’s in one of the most tightly regulated food markets in the world. Imagine what it’s like in the U.S.

And even among real honey, a lot is contaminated. Many beekeepers use chemicals and medications in their hives. Once you introduce those substances into the hive, they end up in the honey.

Search “pesticide residue in honey” and you’ll find tons of USDA and university studies showing American honey is contaminated—not just from crops, but from what beekeepers themselves put into the hive.

So, one major benefit of having your own hive is knowing your honey is pure.

Second—bees make the best pets. They don’t bark at night, they require very little upkeep, and they give you honey! The educational value alone is huge, especially for children. That was one of the most meaningful aspects of beekeeping for me.

The Shepherdess:

I’m almost embarrassed to ask this—but I didn’t know there was a difference between conventional beekeeping and natural beekeeping. Could you explain the difference?

Questions about Natural Beekeeping with Dr. Leo Sharashkin:

Absolutely. It starts with the bees themselves—and the type of hive you use.

In the U.S., bees were brought over from Europe hundreds of years ago. Since then, they’ve acclimated to the environment here. But there’s huge variation in their genetic makeup. Bees are incredibly adaptable from one generation to the next.

Genetically, honeybees have 40 times more recombination per generation than humans. This high genetic variation allows them to quickly adapt to local conditions: bloom times, climate, winters, drought.

Now, if you let bees live naturally for a few generations—no interventions—they adapt beautifully to their environment.

But in commercial beekeeping, it’s a different story.

Most bees sold in the U.S. are bred in southern states like Florida, where winters are mild. Bee breeders start selling in February, and they ship packages north to Michigan, Missouri, wherever. These bees often have queens from the Italian strain, native to the Mediterranean—a climate with mild winters and ten months of flowers.

So what happens? These bees do fine in summer, but they’re not in sync with northern climates. They don’t survive winter well, and the beekeeper has to buy new bees each spring. The cycle repeats.

Then there’s disease resistance. In the wild, if a new parasite like varroa mites shows up, bees either die—or the survivors develop resistance. That’s natural selection.

But in commercial beekeeping, they can’t afford to let 95% of their colonies die to find the best survivors. They have contracts—pollinating almonds, producing honey. So they treat all their bees, year after year, never letting natural selection work.

So today, 20 years after varroa mites arrived, they’re still a huge problem—because the bees have never been allowed to adapt.

When people ask me, “What do you do about small hive beetles? About varroa mites?”—I say, “I do nothing.”

Why? Because my bees came from the woods. They were already surviving on their own.

The Shepherdess:

It’s good. Alright, so we have a question here, and it’s a little bit long—let me see if I can get it out. David says:

“Dr. Leo, while acknowledging that many bees now are partially mixed with Africanized bees and that this makes them robust, is there any concern about the level or mix of that strain in wild swarms, and how would one recognize this?”

Dr. Leo Sharashkin:

Yes, thank you. Africanized bees are a cross between the European honeybee and the African honeybee. This was done in Brazil, and over time they migrated north through Latin America, into Mexico, and eventually into the United States.

The good news is that this strain—while very aggressive—cannot survive in the north. Even in Missouri, they don’t make it through the winter. So if you’re in zone 6 or further north, it’s not a concern. Even in zone 7—places like Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky—it’s almost not a concern.

The areas where you need to be careful are places like Arizona, Florida, and Texas—the far south. But even there, many beekeepers manage fine. I translated a great book from French called From the Earth, which shows how bees are kept in 23 different countries—including places like Mexico where the only bees available are Africanized. They can be kept productively; you just need very good protective gear and large smokers.

Of course, you wouldn’t want to keep very aggressive bees near homes or livestock, but they are healthy, productive bees. If you can keep them away from human activity, and if you don’t mind the intensity of interaction, it can be done. Many bees will swirl like a tornado trying to sting you—not very pleasant. I don’t wear protection when I harvest honey from my bees, but it’s doable.

Also, if you read the literature, you’ll find that some Africanized bee colonies are becoming more gentle over time. So you may not even be able to tell without a genetic analysis.

That said, I believe beekeeping should be joyful. So if you have a hive that constantly gives you grief—extremely aggressive or defensive—just requeen it with a more gentle stock. I’ve never had to do that myself. I actually like the mean hives because if they can defend themselves from me, they can defend themselves from bears, opossums—you name it.

The Shepherdess:

Yeah, good question here from Alan. He says: “What is your opinion on Top Bar hives?”

Dr. Leo Sharashkin:

Yes, I’ve kept bees in Top Bar hives, and they are excellent in the South. For those unfamiliar, a Top Bar hive supports the comb only from the top bar—a single plank of wood. There’s no frame structure surrounding the comb.

That’s both an advantage and a limitation. The advantage is that Top Bar hives are inexpensive and simple to build. They’re used in places like Africa where people can’t afford framed equipment.

But because the comb is only supported from the top, you can’t make the hive very deep. If the comb gets too long, the weight of the honey will cause it to collapse. So Top Bar hives have to be shallow. Because of that, I do not recommend them for cold climates. The depth of the comb is important for successful wintering.

Another consideration: with frames, once bees build and fill them with honey, you can spin them in a honey extractor—a centrifuge that removes the honey without damaging the comb. You can return that intact wax to the bees so they don’t have to rebuild it, which significantly increases productivity.

In a Top Bar hive, the comb is usually crushed and strained, so the bees have to rebuild it each time. That means more wax, which is great if you need wax, but less honey overall.